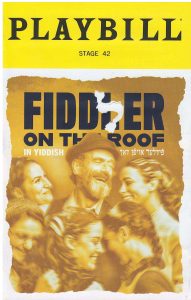

Last summer, Battery Park was busier than usual on July 4th. In addition to the crowds who had come to see fireworks explode around Lady Liberty, all the lights were also on at the Museum of Jewish Heritage (MJH). Manhattan luminaries, arriving in limousines and via car services, were there for the opening night of the first American production of the Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof.

Last summer, Battery Park was busier than usual on July 4th. In addition to the crowds who had come to see fireworks explode around Lady Liberty, all the lights were also on at the Museum of Jewish Heritage (MJH). Manhattan luminaries, arriving in limousines and via car services, were there for the opening night of the first American production of the Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof.

Two weeks ago, after extending its original run several times, the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene’s production moved to Stage 42 (an Off-Broadway theatre on 42nd Street). Much to the amazement of sceptics everywhere, the Folksbiene (housed at MJH) had taken Shraga Friedman’s adaptation—which had played for about a year in Tel Aviv way back in 1965—and transformed it into a local phenomenon. Over and over again, critics have applauded its “authenticity.” According to Jesse Green’s review in the New York Times: “it offers a kind of authenticity no other American ‘Fiddler’ ever has.”

I saw the Folksbiene’s production at Battery Park twice, once with friends on July 5th just to enjoy and once by myself a few weeks later to fact check. The second time I went, I was sitting next to an exuberant “baby boomer” from New Jersey. When she came back from the ladies room at the end of the intermission, she told me she loved it. When I asked her why, she said it was “so authentic” in Yiddish. “Do you think Les Miz would be better in French?” I asked. Luckily, the music cue saved me from her angry glare, and I didn’t dare bother her with any additional questions after the curtain call.

So almost everyone agrees that Yiddish Fiddler is “authentic,” but by what standard? What does “authentic” actually mean in this context? What are people implicitly comparing Yiddish Fiddler to when they call it “authentic”?

- To a Broadway musical first performed—in English—in 1964, and now revived regularly all around the world in a wide variety of languages including Japanese and Thai?

- To an Oscar-nominated musical released—in English—in 1971, and now screened as a sing-along (complete with a costume contest) every Christmas Eve in LA?

- To a Yiddish film called Tevye that premiered—in the shadow of Kristallnacht—in 1939?

- To an Israeli version called A Fidler Afn Dakh first performed—in Yiddish—in 1965?

- To a silent film called Broken Barriers released in the USA in 1919, not to mention all the cinematic versions that came after it in German, Hebrew, and Russian?

Solomon Rabinowitz (best known today by his pen name Sholem Aleichem) published his eight Tevye stories—in Yiddish—at irregular intervals between 1895 and 1916 (the year he died). If he is watching us now from “The Great Beyond,” I am sure Rabinowitz is astonished by the worldwide embrace of Tevye and his family since Fiddler’s premiere in 1964. His dairyman has achieved the status of an icon, but each adaptation takes liberties with his original stories, each in its own way. In some versions, for example, Tevye has seven daughters. In some versions, Tevye has five daughters. In some versions, Tevye only has two daughters. So which version is the “authentic” version? Before you tell me that everyone in the know knows that Tevye had seven daughters, let me remind you that Sholem Aleichem only wrote stories about five daughters… the five daughters named in Fiddler on the Roof. He never told us anything about the other two daughters (one of whom never even got a name).

Fiddler on the Roof, directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins and first performed in English in 1964, has been a source of controversy from the very beginning. Well-known Jewish authors were incensed. In his review for Commentary magazine, Irving Howe described Robbins’s Anatevka as “the cutest shtetl we’ve never had.” Philip Roth called Fiddler “shtetl kitsch.” Nevertheless, people loved it. According to Robbins, his father (who had fled from the village of Rozhanka in 1905 at the age of 18) embraced him backstage on September 22, 1964—Opening Night on Broadway—and asked in a tearful voice: “How did you know?” Thus was their fraught relationship finally healed. By the time Fiddler closed in 1972—after 3,242 performances—it had become the longest-running show in Broadway history.

No wonder people nowadays are always surprised to hear that initial reviews were lukewarm, with most of the praise going to Zero Mostel’s performance as Tevye. The first person to review Fiddler when it opened in Detroit in June 1964—a critic from Variety—wrote: “There are no memorable songs in this musical.” When it opened on Broadway in September 1964, Walter Kerr of the Herald Tribune sniffed: “I think it might have been an altogether charming musical if only the people of Anatevka did not pause every now and then to give their regards to Broadway…”

On his “Broadway Scorecard,” Steven Suskin, the author of Opening Night on Broadway: A Critical Quotebook of the Golden Era of the Musical Theatre, shows two rave reviews and four favorable reviews. “Here was a classic made brilliant by an imaginative production, rather than the material itself,” says Suskin on page 209. Suffice it to say, however, that I believe it was “the material itself,” material which has proved more than resilient in every kind of production no matter the budget and regardless of the strength of each cast. Whatever the circumstances, Fiddler always wins.

So what makes Yiddish Fiddler feel so “authentic” to so many even if it isn’t? I’ve given this question a great deal of thought since July and I honestly don’t think it’s the language factor. Although some of us remember the sound of our grandparents speaking Yiddish when we were young, very few people in the audience actually speak Yiddish themselves. Most of the cast members—some of whom are not Jewish—had to be coached syllable-by-syllable from scratch. However, everyone is so familiar with the basic elements of song and story that they react to the onstage goings on before they even have time to read the supertitles—in English and Russian—that are flashed on big screens on both sides of the stage. There is so much physical comedy in Act One and so much pathos in Act Two that words—in any language—are almost irrelevant.

I think New Yorkers are so used to seeing bombastic productions that the small scale of Yiddish Fiddler creates an unexpected and overwhelming intimacy. Director Bartlett Sher staged his 50th anniversary production—in 2015—at the Broadway Theatre on 7th Avenue. The sets in the 1,763 seat Broadway Theatre were enormous and while the new choreography by Hofesh Shechter was superb, the dancers were almost too good. The stage was way down there, while the audience went up to the rafters.

By contrast, Safra Hall—the auditorium at MJH—has 375 seats, and director Joel Grey has scaled everything down accordingly. The set design by Beowulf Boritt is minimal, leaving more to the imagination. Choreographer Stas Kmiec has streamlined and humanized Robbins’s dances. In the second performance I saw, one of the dancers even dropped his bottle during the beloved Bottle Dance at the end of Act One. Whether by accident or intention, it was a charming touch. Ann Hould-Ward’s clever costumes subtly color-code the three daughters and their mates, so even in crowd scenes we always know who belongs in which couple. The barrier between actors and audience gently fades away until, by the end, everyone is an Anatevkan. When the house lights go up, we are all disoriented strangers “in a strange new place” if only for a moment.

The seating capacity of Stage 42 is 499, but I went last week, so I can assure you now that the transfer is just fine. The high stadium seating reduces the intimacy a bit, but the sight lines are much better. And the enhanced Lighting Design by Peter Kaczorowski is superlative, adding enormous emotional depth to the somewhat larger stage.

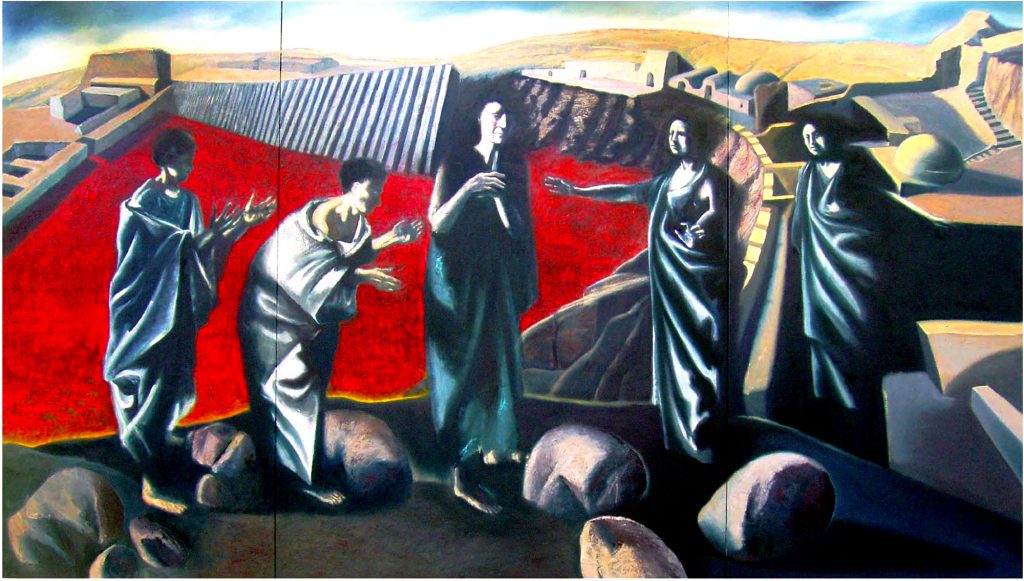

In these tumultuous times, it feels good to spend a few hours in Anatevka, but we must keep our wits about us. It’s tempting to idealize the place and think that everything was simpler there, but it was never so. People who have read their Sholem Aleichem know the fates of the two daughters who don’t get their own story lines in Fiddler. Shprintze drowns herself after her Jewish suitor deserts her. Bielke marries a rich man—also Jewish—who turns out to be a swindler, and she winds up in America making stockings in a sweat shop.

The Tevye stories are about cultural implosion as well as anti-Semitic expulsion, and Fiddler on the Roof honors this razor’s edge in the “horse/mule” battle during the musical prologue “Tradition,” as well as in Yente’s number “The Rumor” in Act Two. “Every Jew has two Congregations: The one he belongs to and the one he will never set foot in.” When we are honest with ourselves, we know problems beset us from both within and without. And this is precisely why Fiddler on the Roof in any language never was—and never will be—simple nostalgia.

© Jan Lisa Huttner (2/26/19) FF2 Media

Jan Lisa Huttner has self-published two books about Fiddler on the Roof, Tevye’s Daughters: No Laughing Matter and Diamond Fiddler: Laden with Happiness & Tears. She is currently serving as a consultant on the new documentary Fiddler: The Amazing Story of Fiddler on the Roof (due in theatres this May).